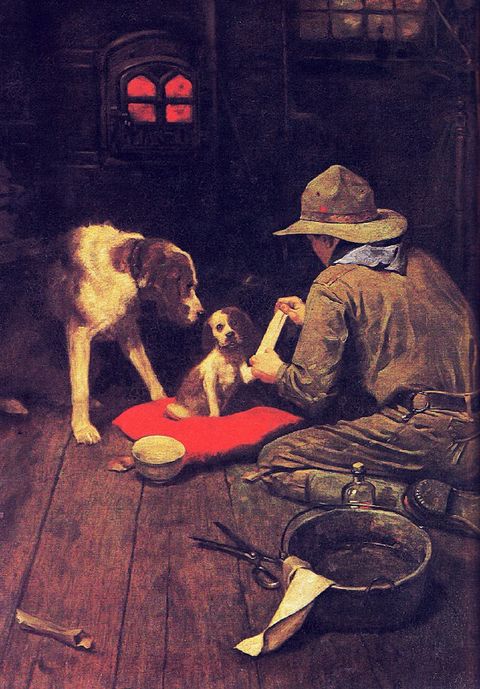

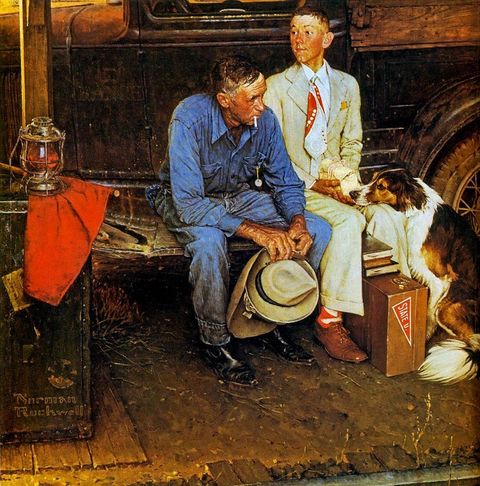

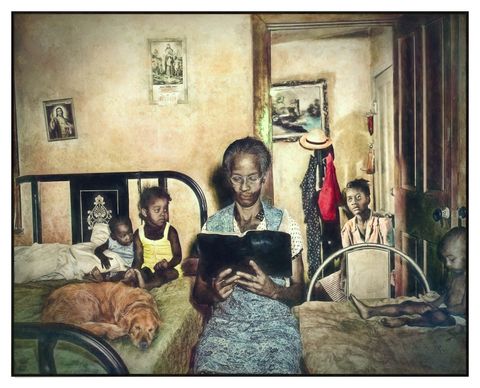

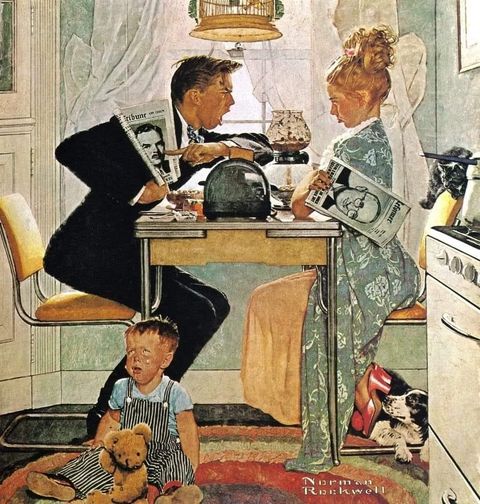

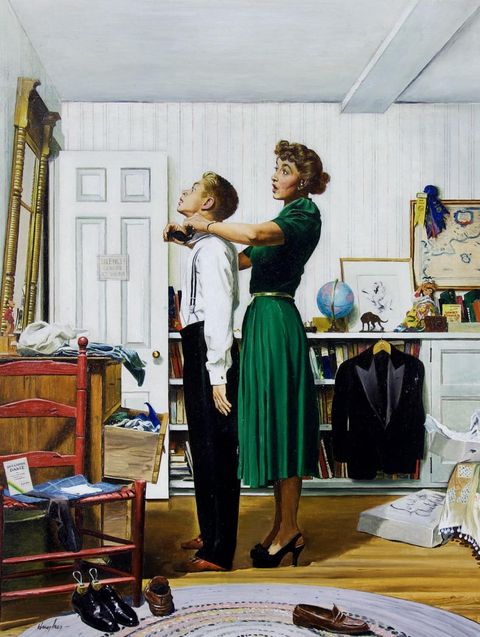

(ENG below) Как-то я совсем забыл про Norman Rockwell. Я ж даже на Saturday Evening Post подписан, и вообще мой поход в Библиотеку Конгресса за архивами этого журнала начался именно с этого художника. Вот так делались иллюстрации на обложку журнала — художник писал маслом крупноформатную картину на злободневную тему, дальше ее фотографировали, и помещали на обложку, а он шел делать следующую. И посмотрите с какой любовью к деталям! Вот уж не назовешь рутиной. Ушла эпоха, теперь и художники другие, и работа их выглядит сильно иначе. К каждой картине шла либо история, либо это было самовыражением художника, поднимающим тиражи. Например, девочка с фингалом — это натурщица Мэри Уэлен-Леонард, дверь директора школы и антураж — из школы Cambridge, New York. Причем художник умудрился физически вывезти дверь из школы к себе в студию. Некоторые картины — иллюстрации к историям журнала. Но мне кажется, все его картины рассказывают историю, выдуманную или реальную, и потому их интересно рассматривать.

В 1943 году пожар в его студии уничтожил все работы, которые там хранились, а также костюмы и реквизит, собранные за многие годы. Также была уничтожена его коллекция трубок. Роквелл говорил, что мог случайно уронить уголек из своей трубки на стул, который стоял под выключателем света, когда он выключал свет и покидал студию той ночью. Друзья, которые приходили к нему в студию, говорили, что у него была привычка зажигать трубку и бросать спичку в большой железный горшок, где он хранил тряпки, смоченные в терпентине.

Даже до пожара Роквелл выбрасывал некоторые из своих оригинальных масляных картин и эскизов. Он отправлял картину в “Saturday Evening Post” для обложки, и когда она возвращалась, он срывал холст с рамы, выбрасывал его и натягивал новый холст на раму для следующей картины.

Когда одна из поклонниц написала ему с просьбой купить некоторые из его оригинальных работ, он назвал её “сумасшедшей женщиной из Чикаго” и взял с неё 100 долларов за каждый из семи холстов. Семья “сумасшедшей женщины” продала картины в 1990-х годах за 17 миллионов долларов.

#artrauflikes

I completely forgot about Norman Rockwell. I’m even subscribed to the Saturday Evening Post, and it was this artist who actually sparked my venture to the Library of Congress for archives of this magazine. That’s how magazine cover illustrations were made— the artist painted a large-scale oil painting on a topical subject, then it was photographed and placed on the cover, and he would go on to make the next one. And look at the attention to detail! It’s certainly not routine. That era has passed; now the artists are different, and their work looks quite different too. Each painting was accompanied either by a story or served as a form of self-expression by the artist, boosting circulation. For example, the girl with the black eye was the model Mary Whalen Leonard, the principal’s door and the setting were from a school in Cambridge, New York. The artist even managed to physically transport the door from the school to his studio. Some paintings were illustrations for stories in the magazine. But I think all his paintings tell a story, whether fictional or real, and that’s what makes them interesting to look at.

In 1943, a fire in his studio destroyed all of the work stored there, as well as costumes and props that he had collected over the years. Also destroyed was his collection of pipes. Rockwell said that he may have dropped an ash from his pipe onto a chair that sat under the light switch when he turned off the lights to leave the studio that night. Friends who visited him at the studio said that he had a habit of lighting his pipe and then tossing the match into a large iron pot in which he stored his turpentine rags.

Even before the fire, Rockwell discarded some of his own original oils and sketches. He would send a painting to the Saturday Evening Post to be used for a cover and, when it was returned, he would rip the canvas off the frame, toss it away and stretch a new piece of canvas onto the frame for the next painting.

When a fan wrote to him, asking if she could buy some of his original work, he called her, “the crazy woman from Chicago” and charged her $100 a piece for seven canvasses. The “crazy woman’s” family sold the paintings in the 1990s for $17 million

#artrauflikes